South Africa

General Context

South Africa is a country known for its rich cultural, religious and linguistic diversity. The majority of this nation is composed of a plethora of African cultural and linguistic groups. Smaller populations of South Africans comprise people who are descendants of European colonial settlers; descendants of slaves who are of multi-cultural heritage stemming from Africa, South East Asia and European ancestry; as well as descendants of Indian indentured labourers from the 19th Century.

Prior to the advent of democracy in 1994, South African citizens were subject to three centuries of colonial rule under the Dutch East India Company and the British Empire. From 1948 until 1994 the Apartheid regime was implemented by the pro-Afrikaner National Party government. Apartheid, directly translated from Afrikaans, means ‘apartness’. Under apartheid, colonial segregationist policies were enforced with intense authoritarianism, which affected all aspects of public life. The separate development of the different racial groups in South Africa cemented the power and ‘supremacy’ of white South Africans. A product of Apartheid laws and policies, for example, were the forced removals of the 1960s and 1970s, where over 60 000 residents of District Six were forcibly removed from their homes. Sites of forced removal include not only District Six, but numerous other places across South Africa.

In tandem with political resistance movements such as Black Consciousness, the African National Congress, the Pan-African Congress, the United Democratic Front and the Black Sash, among many others, the arts became an important site of struggle. Apartheid public educational policies meant that art was taught formally only at ‘White’ schools and art syllabi were Eurocentric. In response to this, numerous community art organisations and initiatives were established for collective artistic education and exploration. Many artists also maintained life-long independent art practices. Despite the systemic obstacles posed by the government and public institutions, Black artists working in South Africa produced art that not only challenged the oppressive and violent apartheid regime, but also innovated the field.

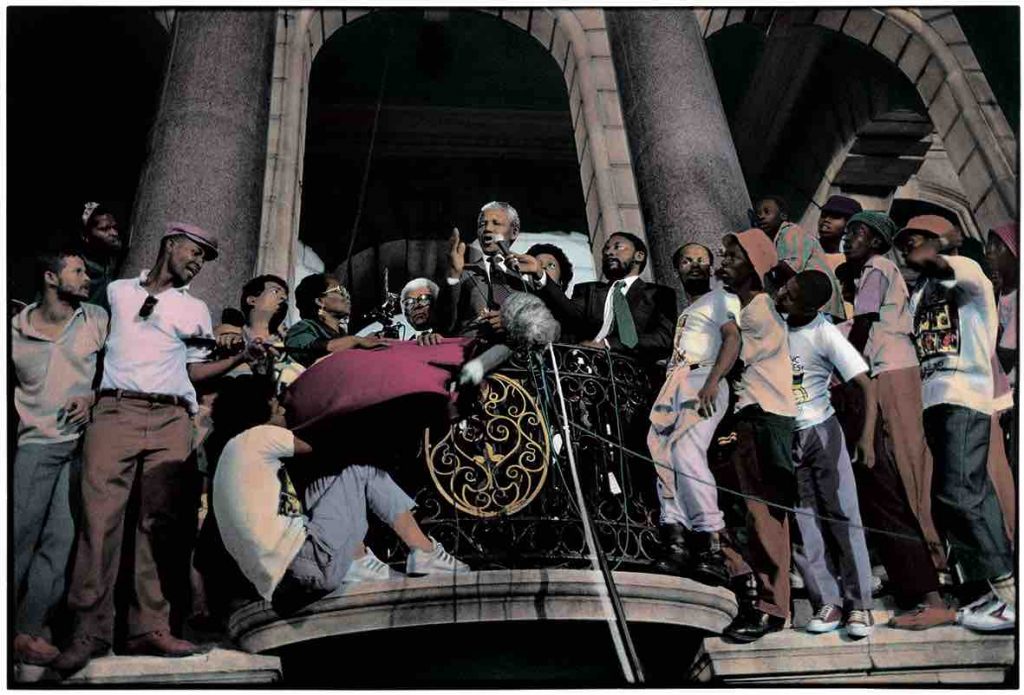

Apartheid came to an end after a series of severe economic sanctions and international outcry following the brutal response to a number of uprisings, including the youth uprising of 1976 followed by the emergence of the Mass Democratic Movement in the 1980s. With the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, negotiations between the National Party and the African National Congress ultimately led to the development of the Democratic Republic of South Africa in 1994 with the first election based on universal franchise.

Nelson Mandela delivers his first public speech in twenty seven years, on the day of his release. City Hall, Grand Parade, Cape Town, 11 02 1990. Photo Chris Ledochowski

The District Six Museum was also established in 1994, following a collective need from the District Six community to gather, remember together and to record their experiences. Today, the Museum continues to work with people and their memories in a multitude of ways. Memory work functions as a pathway to claim a place in history; as a basis for claiming land; as a reminder of resilience in the midst of pain; as a means of validating individual and collective experiences of trauma; as a pedagogical tool and also as a source of inspiration.

Art Practice in South Africa

South Africa’s art scene is a complex reflection of a society that has endured decades of colonial and apartheid suppression. Artists working in the country grapple with a multitude of struggles that include questions of identity, belonging and the aftermath of conflict and post-conflict trauma. South Africa is an extraordinarily diverse cultural landscape of rich talent that has, in recent years, seen much international interest. Against the backdrop of South Africa’s contested vastly political and deeply inhumane past, an incredible portfolio of outspoken, sensitive and engaging artists has emerged – truly rendering art as the ‘memory of humanity’.

Prior to apartheid, and through the colonial lens, the art of Africa and South Africa was perceived as largely ‘tribal’ – exoticised and presented as European art collectors, art historians and anthropologists perceived it, rendering black art and artists invisible. However, the 20th Century saw the establishment of Black artists such as Albert Adams, Peter Clarke, Ernest Mancoba, Gladys Mgudlandlu, George Pemba, Helen Sebidi, Gerard Sekoto, Durant Sihlali and Ernest Cole, among others, who sought to subvert white hegemony and cultivate their own artistic legacies. These artists introduced the human condition from a black urban cosmopolitan perspective and set precedent for a new generation of artists. In addition to this, artists like Esther Mahlangu and have greatly contributed to the artistic legacy of the country, through the continuation of Ndebele traditions and the introduction of these art forms to new audiences.

Many artists and cultural workers who aligned themselves with the anti-apartheid movement, reflected socio-political issues in their work and joined their collective skills to build alternative creative spaces through which a non-racial South African culture was forged. From the late 1970s until the 1994 democratic elections, art became a powerful expressive weapon to mobilise against the might of the apartheid regime.

Local organisations like Community Arts Project (CAP)[1], MEDU Art Ensemble, Federated Union of Black Arts (FUBA), Thupelo Workshop[2], Greatmore Studios and the Bag Factory had far-reaching influence in community civic organisations, schools, churches, teachers and worker’s movements as well as nurturing up-and-coming artists. Many of the artists who participated and contributed to the establishment of the District six Museum trained, taught and/or participated in these art organisations.

Despite this period being intensified by a series of draconian apartheid laws – banning, imprisonment, detention without trial and the state of emergency – artists like Jane Alexander, Lionel Davis, Trish DeVilliers, Bongiwe Dhlomo-Mautloa, Garth Erasmus, David Koloane, Pat Mautloa, Sophie Peters, and Mario Sickle, and were instrumental in affirming the role of art as a tool for social change and raising political consciousness.

Together with cultural organisations they undertook projects that deliberately questioned and re-imagined how contemporary art-making can shaped or contribute to the building of “collective memory” in ways that contest the on-going legacies of apartheid.

Resistance art has largely come to define the genre of the pre-democratic South African ethos in the art scene, it has in the process produced many of South Africa’s finest artists and has ignited a new generation of artists who claim their right to the post democratic space with fervour. Today, South African contemporary artists are internationally sought-after and participate in the international art scene through solo exhibitions at commercial galleries and in museums, in art fairs and biennials.

Memory Work in South Africa

The District Six Museum’s mission is premised on the understanding that the memory of every person is an important human right. Memory is closely tied to a sense of dignity, identity, belonging and general well-being. Asserting “I am” — and that “I am in relation to a particular time and place, even if that place has been reconfigured” — is even more important. In his memoir, South African poet Don Mattera talks about memory as a weapon. This is a powerful reminder that the reclamation of memory is a valid modality in and of itself, and that its power extends beyond nostalgic remembering.

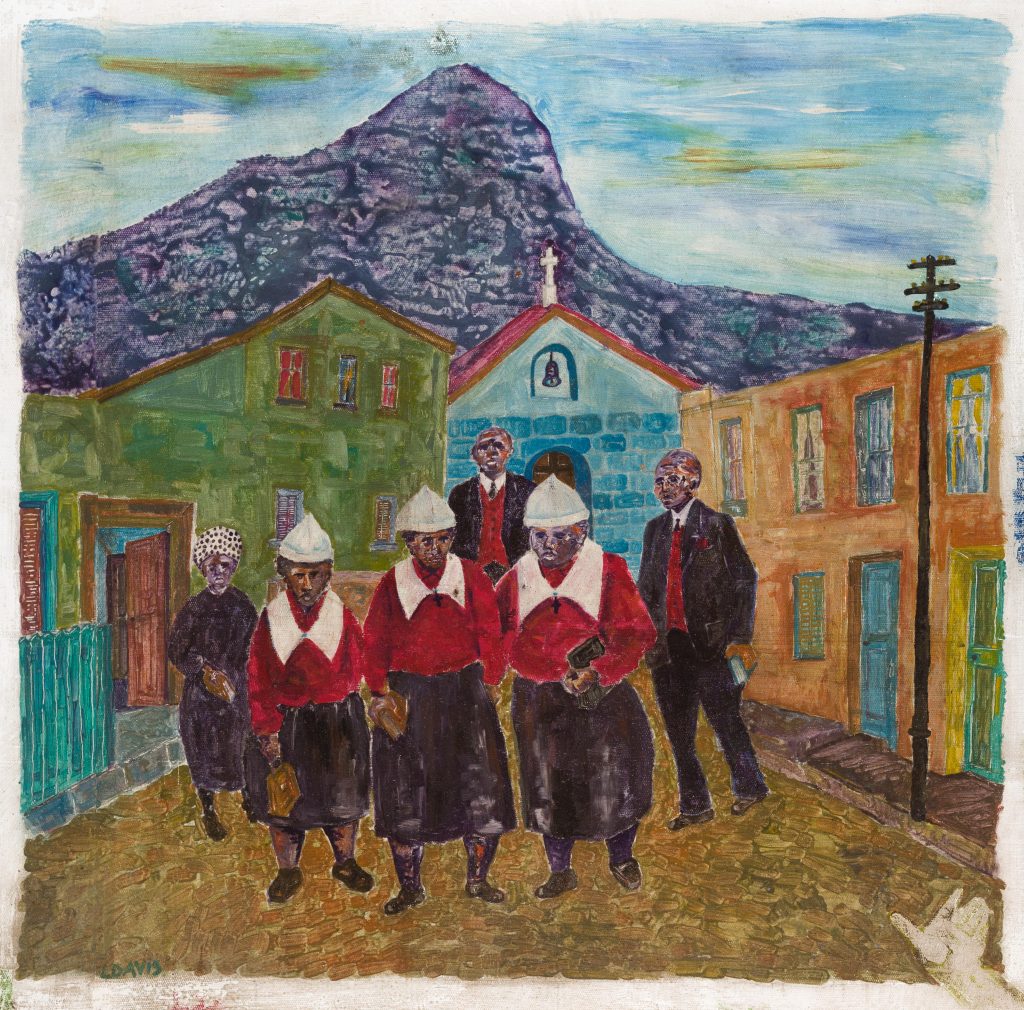

Memory work with victims of forced removals and its collaboration with artists set new important new precedents in the heritage field. With the opening of its inaugural exhibition entitled Streets: Retracing District Six (1994), to its permanent exhibition entitled well as the groundbreaking site-specific Public Art Sculpture exhibition in 1997. Artists such as Peter Clarke, Lionel Davis, Peggy Delport, Fatima February, Paul Grendon, George Hallett and Roderick Saul, amongst many, have played a central role in shaping the on-going aesthetic of the Museum in new and meaningful ways.

District Six Museum permanent Digging Deeper Exhibition, Cape Town – Photo: Paul Grendon

Through exhibition-making and initiating projects with artists and former residents, the reconstruction of memory impacts and contributes to the reconstruction of selves who have been battered and broken by systemic injustice. Mobilising place memory is a strength of the District Six Museum’s methodology and has enabled a large corps of people to reclaim their bonds to the places from which they were wrenched.

The work of memory, in unearthing the past and acknowledging hurt and anger, should be tethered to moral and legal accountability by those actors who profited from segregationist policies, such as forced removal. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), established in 1995, engaged both victim and perpetrator in a protracted search for justice and set in motion a model for working through the past. The TRC, much like the Museum, has become a symbol of the possibilities for moving forward to reclaim joint, equal citizenship. However, we are constantly reminded in the daily work of memory, that this justice feels elusive and remains intangible for victims and survivors.

The transition out of apartheid has been a precarious journey for a nation who had suffered systemic social injustices and gross human rights violations. Apartheid over generations had white washed the histories and cultures of black people rendering it invisible and inferior. Bearing witness through testimony and storytelling, memory has become key to healing a nation grappling to right the wrongs of the past.

Thematic Focus

The District Six Museum has selected the contemporary artists Lionel Davis, Haroon Gunn-Salie, Sophie Peters, and Ayesha Price, for whom memory work is a fertile ground in making art meaningful and to voice their commentary against a shifting cultural and socio-political landscape. Although each artist has emerged and operated within different periods of South Africa’s political and cultural history, together they embody a commitment to memory work and artistic practice that has characterized the District Six Museum since its establishment. Further, each artist seeks to counter ideas of a ‘national South African narrative’ through the engagement with nuance and lived experience.

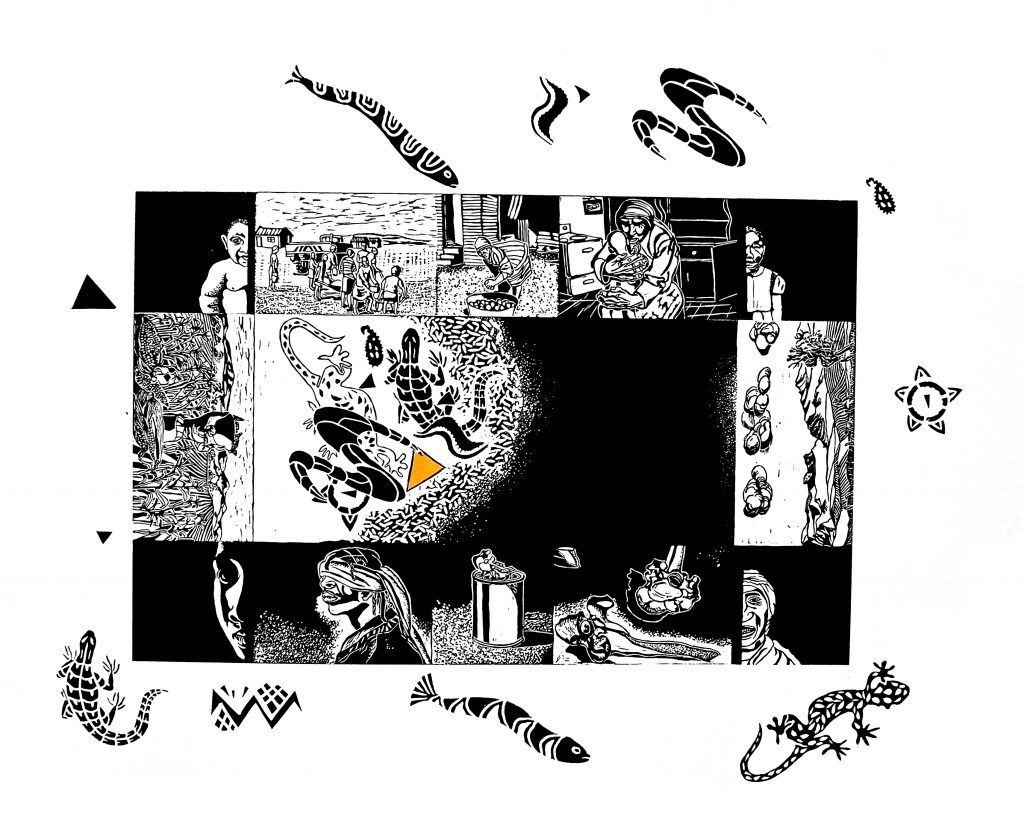

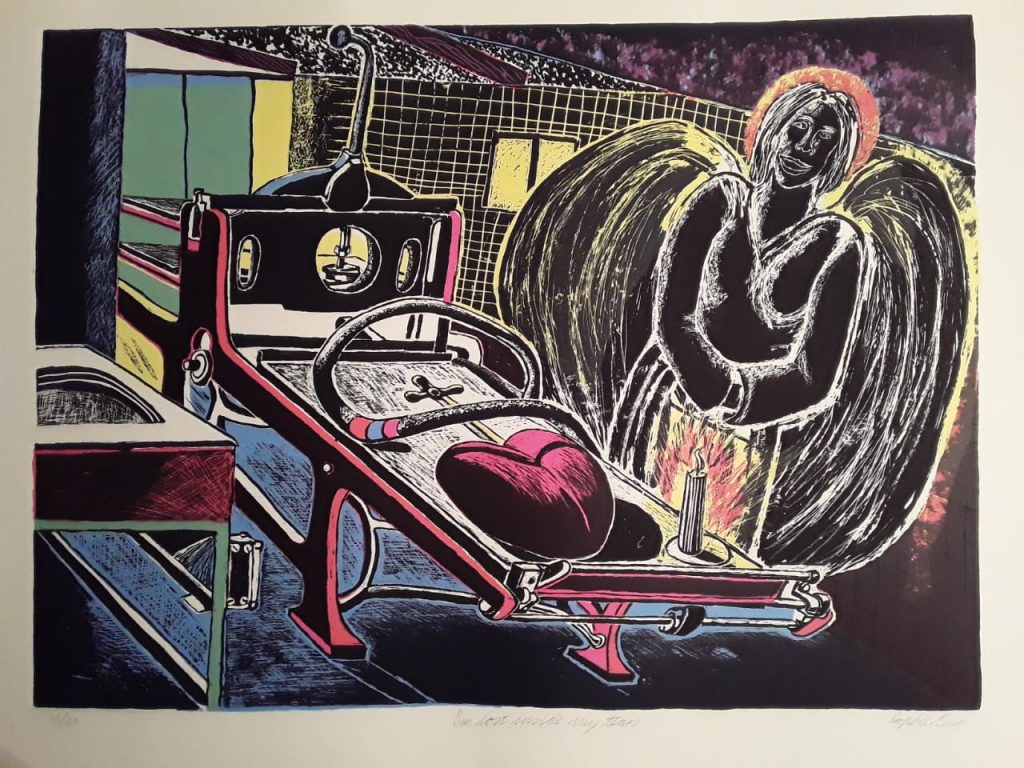

Lionel Davis, as mentioned previously, has a long-standing relationship with the District Six Museum that began with the staging of the exhibition Streets: Retracing District Six (1994). However, Davis began recording the last years of District Six and the process of forced removals long before the Museum’s inception. After his prison sentence on Robben Island, where he was imprisoned for his anti-apartheid activism, Davis returned to District Six where he sketched landmarks, streets and sights before they were systematically destroyed. These images provide a crucial record of life in District Six, and have since been translated and adapted into other artworks, such as linocut prints. Education is also an important aspect of Davis’ practice, and he has mentored a number of artists through his work at Community Arts Project (CAP), the District Six Museum and elsewhere. In 2017 the District Six Museum with the Iziko South African National Gallery produced Davis’ retrospective exhibition Gathering Strands which commemorated his life’s work and activism.

Over the course of his career, Haroon Gunn-Salie has consistently engaged with practices of memory and place-making in South Africa. In 2011, he collaborated with former residents of District Six in his site-specific series titled Witness (2011-), which is part of his presentation here at WAMM. Witness works with former residents’ stories and memories of District Six and their close relation to questions of ‘home’ – the physical and now intangible space which was wrenched from them. Since this series, Gunn-Salie has continued to explore questions of land dispossession, anti-colonialism and protest, addressing major South African events such as the Marikana Massacre in 2012 with his installation Senzenina (2018).

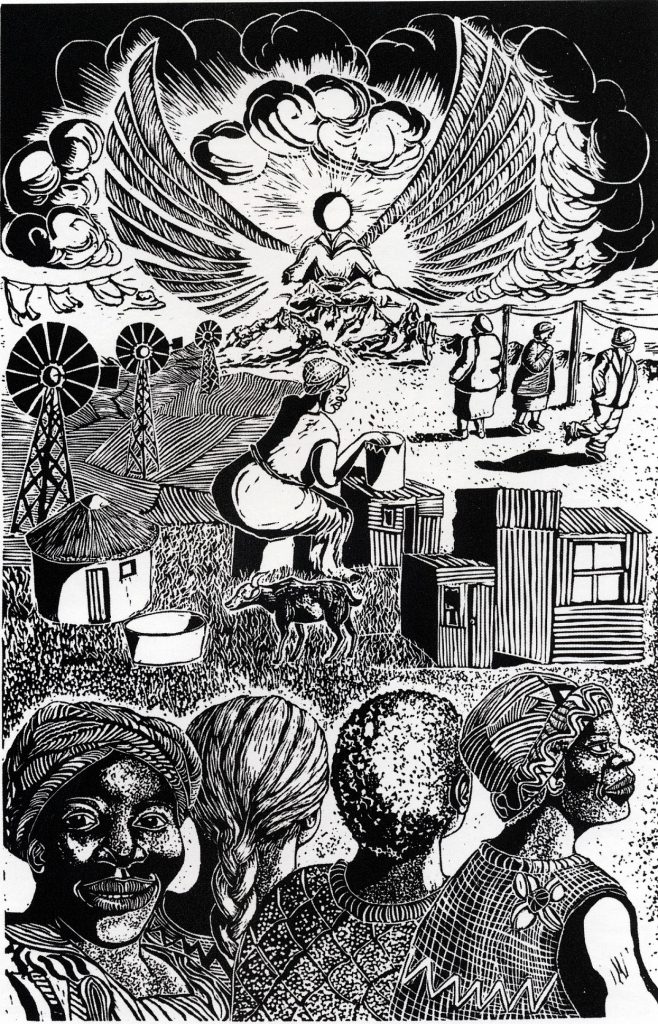

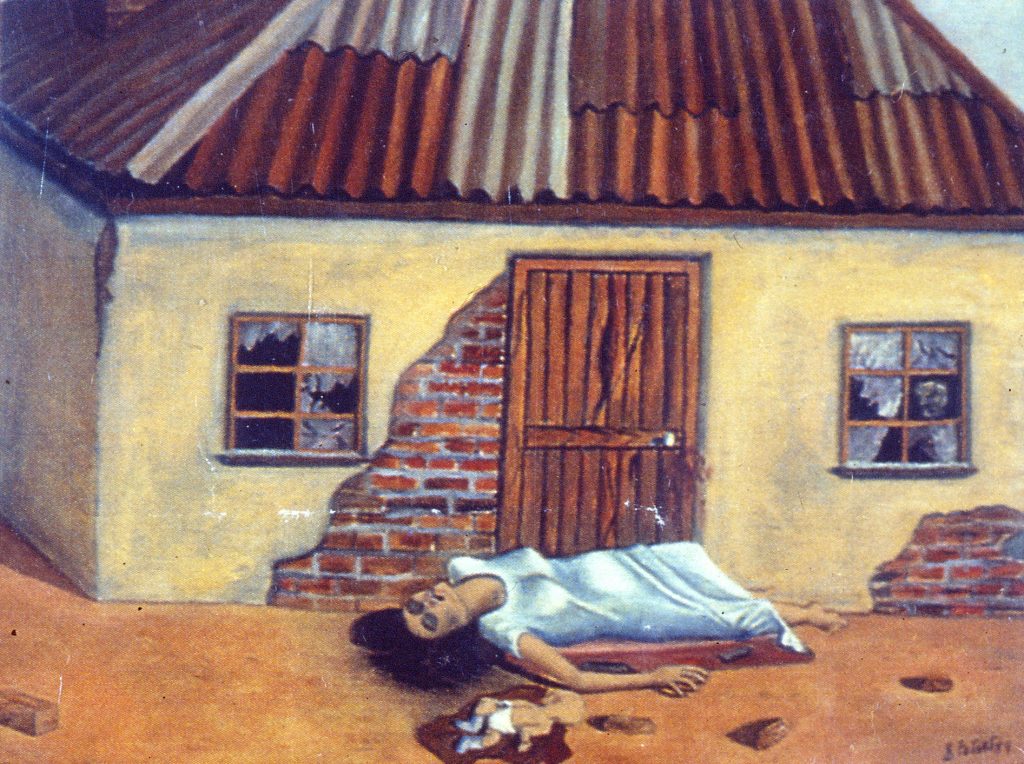

Sophie Peters’ work is informed by her life experiences growing up in apartheid South Africa and her commitment to her Christian faith. As a painter, vivid and detailed storytelling is an important aspect of the work, and through this medium, Peters comes to terms with trials of violence and hardship from her past. Peters’ work demonstrates how working with memory and trauma through art making can stimulate or contribute towards a process of healing. Education is an integral part of her career as an artist, as is the mentorship and support of other artists. In 1996, Peters in collaboration with other artists contributed to the District Six Museum exhibition Displaying the Game (1996) in a mural on children’s street games titled ‘From the Streets to the Field’.

Through her artistic practice, Ayesha Price addresses notions of commemoration, and seeks to problematize the ‘grand narratives’ of history writing. Price’s work is deeply engaged with questions of memory, processes of forgetting, and loss, as it pertains to sites and events in Cape Town and elsewhere in South Africa. Working in photography, video and mixed media, Price offers an intimate perspective of women’s experiences in Islam in Cape Town, for instance, through her works Archiving the Modesty of the Cape Malay Woman: The Medora, 2012 and an affective evocation of the cycles of trauma and injustice in her video installation Save the Princess (2013). Alongside her personal work as an artist, Price also works as an art educator and facilitator. In this role, she has facilitated the creation of the Peninsula Maternity Hospital Memory Project in District Six with former residents of District Six, and with Tina Smith (Head of Exhibitions, District Six Museum), was the co-curator of Lionel Davis’ retrospective Gathering Strands (2017).

In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the declaration of District Six as a ‘Whites Only’ area, Davis, Peters and Price participated in the print exchange project Remembering 60 000 forced goodbyes (2016).

As a key aspect of their practice, the artists collaborate with numerous communities and sectors of the art and heritage scene in South Africa. Implicit in their collective practice is the understanding that memory work is ultimately about the care of people, a deep respect of their experiences, and their right to dignity in an unjust world