Bulgaria

General Context

A Balkan nation boasting of a Black Sea coastline and beautiful mountainous interior, Bulgaria is one of Europe’s oldest countries, the archetype of the cultural melting pot with Greek, Slavic, Ottoman and Persian influences. It has a rich tradition of dance, music, costumes and crafts and has a capital – Sofia – that dates from 5th century BCE. Three Bulgarian kingdoms and five centuries of Ottoman rule gave way to the modern Bulgarian state which aligned with Germany in both World Wars. In the latter half of the 20th century, the country became a one-party socialist state behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ as part of the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc.

This long and turbulent history plays a major role in Bulgaria’s present. However, modern Bulgaria is not just its material heritage of monuments and historic sites; it is a country that transitioned into democracy rather peacefully in 1989, its people embracing the momentum without violence. Since 1989, Europeanisation and integration into modern Europe lies at the centre of Bulgaria’s vision for its future, representing the national consensus among the political forces and society in general. The process of European Integration established new structures and institutions, including the National Parliament, which helps in the balance of power in the centralized system.

Another important aspect is ‘de-communization’ which involves dismantling the legacies of the communist state establishments, culture, and psychology in the post-communist states. Historians have not subjected that 45-year period (from 1944 to 1989) to an in-depth analysis when Bulgaria strictly followed the model of accelerated modernization and development imposed by the former Soviet Union. Some investigative journalists like Hristo Hristov have begun to unveil the curtain of thirty-years long silence on the crimes of forced labour camps that operated within that period.

Read more about Bulgaria:

Explore these independent websites:

Art Practice in Bulgaria

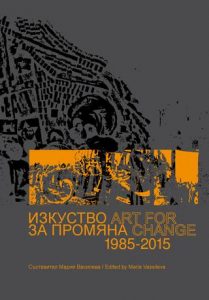

The modern Bulgarian art is a reflection of the transformation of Bulgaria in the last decades. The end of the socialist era marked the liberalization of artistic life, infused with the desire to challenge the status quo unhindered by censorship which many artistic groups experienced during the previous regime. Artists developed individual styles without following common trends. In the late 1980s, terms such as ‘unconventional art ‘ or ‘non-traditional art’ were used to call these new forms of art. They were essentially different in their use of material and expression vis-à-vis the art of the former socialistic regime. Later on, in the 1990s these terms were replaced by the more universal ‘contemporary art’.

During this period of change, contemporary art went through various stages of development by forming of different art groups at regional level. Processes of art-making also evolved, through improvisation and experimentation in open air. As a result, the way this art entered the galleries changed and their public reception grew more complex. One of the groundbreaking exhibitions at the end of the historical era of socialism was ”The City” in 1988, by a group of artists with the same name ‘The City Group’, initiated by Philip Zidarov, Greddy Assa, Svilen Blazhev, Bozhidar Boyadjiev, Andrey Daniel, Vihroni Popnedelev, Nedko Solakov. These artists responded to a specific contemporary situation and realities of everyday life, including political life. Art critic Vesela Nozharova points out that ‘unconventional art was quick to measure the pulse of these changes and reacted as contemporary art should” in the early years after the collapse of the system(1). Many exhibitions during 1988 and 1989 can be viewed as social protests, including Nedko Solakov’s ‘View to the West’ and Vasil Simittchiev’s ‘Ironing the Bulgarian flag’. The formation of the new individual in the post – socialist society has continued to be explored in the films of Adelina Popnedeleva from the Fresh series (2005-2009).

Bulgarian artists and as well citizens have not being able to construct its unified past but issues which are being addressed remain critical creating a reflective space for society to think about itself.

Memory Work in Bulgaria

The past 30 years spent in transitioning from totalitarian regime to democracy, from socialism to capitalism, inspires the memory work in Bulgaria. Similar to many other societies that have gone through traumatic events, there are two conflicting approaches that emerge in dealing with this past: the first one is “reconciliation through forgetting”. The second is where the memory of the past is not brushed aside but examined and accepted. Recalling Santayana’s words that a person who doesn’t learn from the past was destined to repeat it, ‘memory as a duty’ was recognised by the democrats, after 1989. The other argument of the members of the round tables from that period about reconciliation and agreement is supported by the Left members of the society. Thus the memory politics of the recent past, on remembrance lies between these two poles, representing different social groups and legitimising their collective memory.

Although the tremendous gap in Bulgarian historical memory about the communist labour camps in the country due to authentic visual evidences, the archive documents and personal memories of the survivors present powerful image and cognition of the repressions. Among the actors and institutions which enable the narrative of this recent past to come to disclosure is the Committee for Disclosing the Documents and Announcing Affiliation of Bulgarian Citizens to the State Security.

In 2000, National Assembly passed a law on ‘Criminal Nature of the Communist Regime’ and amended it in 2016 with a new law that bans the public display of communist symbols. However, recent newly proposed history books for high-school students in Bulgaria have triggered controversy glaring omissions about the fear, oppression, and desperation that defined the daily existence of many Bulgarians under Communism and whitewashing over the repressive nature of the regime. Thus open the debate on post memory, nostalgia, collective memory and recent social problems the Bulgarian society, especially its youth, experience daily. Artists of different generations presenting commemoration and remembrance search for non-biased approach to recent history, where the border between subjective and objective moments in the transition from living memory toward historical narrative is being challenged.

Explore more about art and memory in Bulgaria:

Read more about memory work in Bulgaria:

- “The Bulgarian Gulag Witnesses” by Ekaterina Boncheva, Edvin Sugarev, Svilen Patov, Jean Solomon

- “Slices of Red” by Krasimira Butseva

Thematic Focus

Remembrance, memory and associated practices thereof are sensitive topics in Bulgaria, often leading to polarisation and even outright denial of certain historical truths. The processes of inherited societal and political practices include nostalgia and general approach in the textbooks presenting the Communist period of Bulgaria are themes, which the presented artists are capturing in their art works. The broad theme of memory and art expression is captured throughout terms/processes of post memory, collective memory and personal memory focusing the narrative in its art expression to contemporary societal processes, but which often derive as attitudes from the past ideologies. Art as a memory trajectory becomes a more coherent approach in the Bulgarian art scene in the last years of 30 years of transition.

The artworks of the six selected artists varies in style and genres, and refer to three major themes :

Theme – Post-memory and the Self – refers to traumatised experience from the Communist repressions and the knowledge about what has happened. In line with the concept of Marianne Hirsch – ”Post-memory” describes the relationship that the “generation after” bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before-to experience they “remember” only by means of the stories, images, and behaviours among which they grew up(2). Hirsch explains the concept of Post-memory referring Holocaust, but this concept could be applied for the explanation of all phenomenon we can explain as Historical Trauma.

Theme – Collective memory – refers to the shared pool of memories, knowledge and information of a social group that is significantly associated with the group’s identity. Collective memory can be constructed, shared, and passed on by large and small social groups. Examples of these groups can include nations, generations, communities among others collective memory can refer to a shared body of knowledge (e.g., memory of a nation’s past leaders or presidents);the image, narrative, values and ideas of a social group; or the continuous process by which collective memories of events change.

Theme – Personal memory – refers to the memory we have of particular items—people, places, things, events, situations—that we have personally experienced. The distinctive feature of personal memory is that it is memory of items that you have experienced for yourself, in the loose and broad sense of “experience”(3).

Academic articles related to the Bulgarian thematic focus:

- “Belene: remembering the labour camp and the history of memory” by Daniela Koleva

- “Collective Memory and Justice Policy. Post-socialist Discourses on Memory Politics and Memory Culture in Bulgaria” by Ana Luleva

- “Excavating the Psyche: A Social History of Soviet Psychiatry in Bulgaria” by Julian Chehirian

- “How to Handle Nostalgia: Georgi Gospodinov and the Reinvention of the Bulgarian Literary Hero” by Miglena Dikova-Milanova

- “Reclaiming a Memory: An Inquiry into the Bulgarian Camp Past” by Lilia Topouzova