Lebanon

General Context

After a succession of Arab, Crusader, and Mamluk rule during the Middle Ages, the geographic regions comprising modern-day Lebanon, including Mount Lebanon and the Mediterranean coastline adjacent to it, fell under Ottoman rule in the 16th century. They remained part of the Ottoman Empire until its collapse during World War I, after which the French Mandate of Lebanon and Greater Syria began. The State of Greater Lebanon was formed under French Mandate in 1920, after Beirut, Tripoli, and parts of Southern Lebanon and the Bekaa were added to Mount Lebanon. Upon independence from the French Mandate in 1943, the Lebanese Republic was established with a confessionalist parliamentary government, granting representation for the major religious sects.

The contemporary history of Lebanon is marked by recurring periods of instability and violence. Between 1975 and 1990, the country witnessed a violent civil war, marked by intranational sectarian fighting, and foreign involvement. The root causes of the war include factors relating to the country’s ethno-sectarian make-up, widening socio-economic disparities, the Arab-Israeli conflict, heavy armament of the Palestinian resistance groups in Lebanon, and ideological divisions between the Lebanese political parties and religious sects. The Israeli army invaded Lebanese territory south of the Litani river in 1978, before launching its invasion of Beirut in 1982, culminating in a siege that effectively expelled the Palestine Liberation Organization from Lebanon; the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon would last 18 years. In 1989, the Taif Accord enforced a cessation of the fighting and the war came to a formal end. Arms were rested after the country had witnessed more than 150,000 casualties and 17,000 disappearances. Israeli occupation, Syrian hegemony and military presence, economic and monetary collapse, damaged infrastructure, massive destruction, large numbers of internally displaced families, forced migration, and continuing ethno-sectarian fracturing defined the war’s immediate aftermath.

During the relatively stable period of time that succeeded the end of the war, major reconstruction projects were initiated by Lebanese politicians in collaboration with the Syrian regime. Marked by a turn towards mass privatization and wide-reaching systemic corruption, these reconstruction projects, such as the joint-stock company Solidere in charge of rebuilding the Beirut central district, plunged the country into great public debt owed to international agencies and local private banks. In February 2005, the assassination of prime minister Rafic Hariri sparked deeper divisions and renewed cycles of upheaval. Two opposing parliamentary blocs, known as March 14 and March 8, emerged; the former called for an end to Syrian hegemony and armed presence in Lebanon, while the latter consolidated its allegiance to the Syrian regime. This opposition threw the country into extended political unrest in the following years. A series of assassinations targeted prominent March 14 leaders known for their anti-Syrian regime political stances. In July 2006, Israel attacked Lebanon, resulting in a 34-day conflict known as the July War, which resulted in the death of over 1500 Lebanese people and 165 Israelis. On the Lebanese front, the July War was fought primarily by Hezbollah, part of the March 8 camp, which allowed it to bolster its position in Lebanese political life following the conclusion of the war. The post-2006 period is marked by frequent political deadlocks. Despite the Doha Accord in 2008, instability persisted and escalated with the emergence of the Syrian civil war after the suppression of the Syrian uprising by the Assad regime, and the resulting influx of Syrian refugees, which stoked nationalist sectarian rhetorics and regulations in Lebanon.

In October, 2019, civilians of diverse socio-economic classes and from different parts of the country, took to the streets to participate in the greatest uprising in the modern history of the country. They rose against the political ‘oligarchy’ that has been in power since the civil war and brought the country to a state of complete economic ruin. The discourse arising out of the uprising rose against the reality of economic deprivation, extreme inequality, reduced life chances and opportunities, proposed increase in taxation, failing infrastructure, withering social security, colossal public debt, high levels of corruption, and suppression of public liberties.

Read more about Lebanon:

Contemporary Art practices in Lebanon

Prior to the 20th century, Lebanese art was limited to artisanship. Decorated cutlery, pottery, mosaic, embroidery, and fabrics were all highly requested crafts from Lebanon. This artisanal tradition was kept alive throughout Lebanon’s modern history and has had a strong revival through designer/artisan collaborations and ceramist/artists creations that have placed Lebanese crafts-making on the international design platforms. Many designers have played key roles in this revival, including Karim Chaaya, Karen Chekerdjian, Nada Debs, Mary-Lynn Massoud and Rasha Nawam, Wyssem Nochi, Ranya Sarakbi, and Najla el Zein.

As of the 20th century and for decades to come, visual art production echoed the international currents of their times. Art academies and university art programs were developed only in the second half of the century. Painting, sculpture and mixed media were the predominant mediums, as a rich modernist tradition was built with artists exhibiting in private galleries, art salons, and in Lebanon’s annual Salon d’Automne, as of the 1960s. Some notable Lebanese artists of the 20th century include Shafic Abboud, Yvette Achkar, Etel Adnan, Hugette Caland, Daoud Corm, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Saliba Douaihy, Gibran Khalil Gibran, César Gemayel, Paul Guiragossian, Seta Manoukian, Aref el Rayess.

At the turn of the 20th century, new forms of expression dominated the Lebanese art production whereby artists approached their subject-matter by rethinking the role of the artist as historian and researcher. Art emerging out of Lebanon in the 1990s and onwards has been shaped by the violent and prolonged effects of the civil war (1975 – 1990). Lebanese postwar art forged various methods for addressing issues of memory and remembrance through artforms that critically respond to the specific socio-political conditions and the structures of feeling of the time. This allowed for complex modes of expression that coalesced into a multifaceted artistic current, against a dominant culture of forced amnesia that suppressed a period in history, ostensibly in order to serve a process of national reconciliation. The act of remembering became a significant political gesture during the nineties, and perceptive artistic propositions challenged the crises of historical representation. Trenchant artistic projects were pursued; some relied on documentary, archival, and research-based methodologies, utilizing an array of aesthetic strategies in video, installation, performance and urban intervention, while others took more formal directions, with painting and sculpture as their mediums.

The work of several Lebanese artists was read through the pervarding post-modern lenses of the time, such as Walid Sadek’s theoretical writings and art installations. Sadek’s work on the civil war as a protracted temporality tackles memory as a living entity, and outlines a theory for a postwar society “disinclined to resume normative living,” by articulating the un-representability of trauma or commemoration. His publication, Bigger Than Picasso (1999) is a pocket-sized ludic and provocative publication with text and image that addresses continuing political violence in post-civil war Lebanon, and centers on a monument built by the Lebanese state in dedication to the Syrian president Assad. Themes engaging with war and its prolonged effects were addressed in various degrees of depths in the oeuvres of the movement’s principal artists, such as Walid Raad’s seminal archival work through the Atlas Group, considered pioneering in its parafictional methodologies; Lina Majdalanie and Rabih Mroue’s performance work that questions theater as an art form capable of operating between fact and fiction; Jayce Salloum, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Lamia Joreige, and Akram Zaatari’s video and film work; Jalal Toufic and Tony Chakar’s writing and installations; Ayman Baalbaki expressionist urban paintings and portraits; and Samir Khaddaj’s mixed-media paintings grappling with the state of uncertainty produced by the war.

War becomes a foundational moment in our historical becoming as seen by Ziad Abillama in his site-specific punctual installation Where Are We (1992) which is composed of discarded weapons and commercial objects placed on a beach cleared of rubble. In Cast of a Bullet Hole from a North/South Wall Situated on the Green Line, Beirut (1995), Paola Yacoub performs a sculptural gesture that refers to the act of sniper shooting, in an attempt to make sense of the intentions of the agents despite an unquestioned passage of time. Fouad el Khoury’s prolific photographic oeuvre, produced in Lebanon from the end of the 1970s onwards, carries stories and traces of battle, bearing witness to the intricate intertwining of war and everyday life, such as in the poetic accounts of the series Beyrouth Aller-Retour (1984). Throughout the 2000s, Nabil Nahas’ collection of cedar paintings adopted the burning of space and soil as a metaphor for the destruction of Lebanon.

Works that came after the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon further contributed to the varied artistic output contemplating war and its afterimages. Such examples include Nada Sehnaoui’s Rubble photography collection and installation which portrayed the raw impact of aerial bombardment, and Marwan Rechamoui’s sculptural work Spectre (The Yacoubian Building, Beirut), a concrete replica of a residential building emptied of its inhabitants, in which the vacancy refers to the lasting violence of wartime displacement. Younger cohorts of artists and filmmakers who came of age after the end of the civil war continue to produce historically minded work that refuses to relinquish agency over an emancipatory retelling of the past. Mary Jirmanus Saba’s A Feeling Greater Than Love excavates the excluded histories of 1970’s workers’ strikes at tobacco and chocolate factories in Lebanon, in the years directly preceding the start of the civil war. Ghassan Halwani’s Erased,___Ascent of the Invisible, is a hybrid documentary and essay film concerned with the unresolved national case of forced disappearances, doubly obfuscated through official strategies of deliberate forgetting.

Thirty years after the declared end of the civil war, the legacy of the conflict continues to permeate the fabric of Lebanese social and political life. Its protracted effects, exemplified by the tight hold of the war’s protagonists on the country’s electoral politics, remain evident in different spheres of life. Through various forms of modern and contemporary art, Lebanese artists have created narratives that inquire upon, criticize, and even challenge hegemonic state-sanctioned policies of amnesia. In the absence of reliable historical texts, and in the absence of close to 75 years of local history in Lebanese curricula, artistic practices strongly contribute to the documentation and uncovering of collective narratives, persistently bringing critical discussion around the civil war period to public discourse.

Explore Lebanon’s art:

Memory work in Lebanon

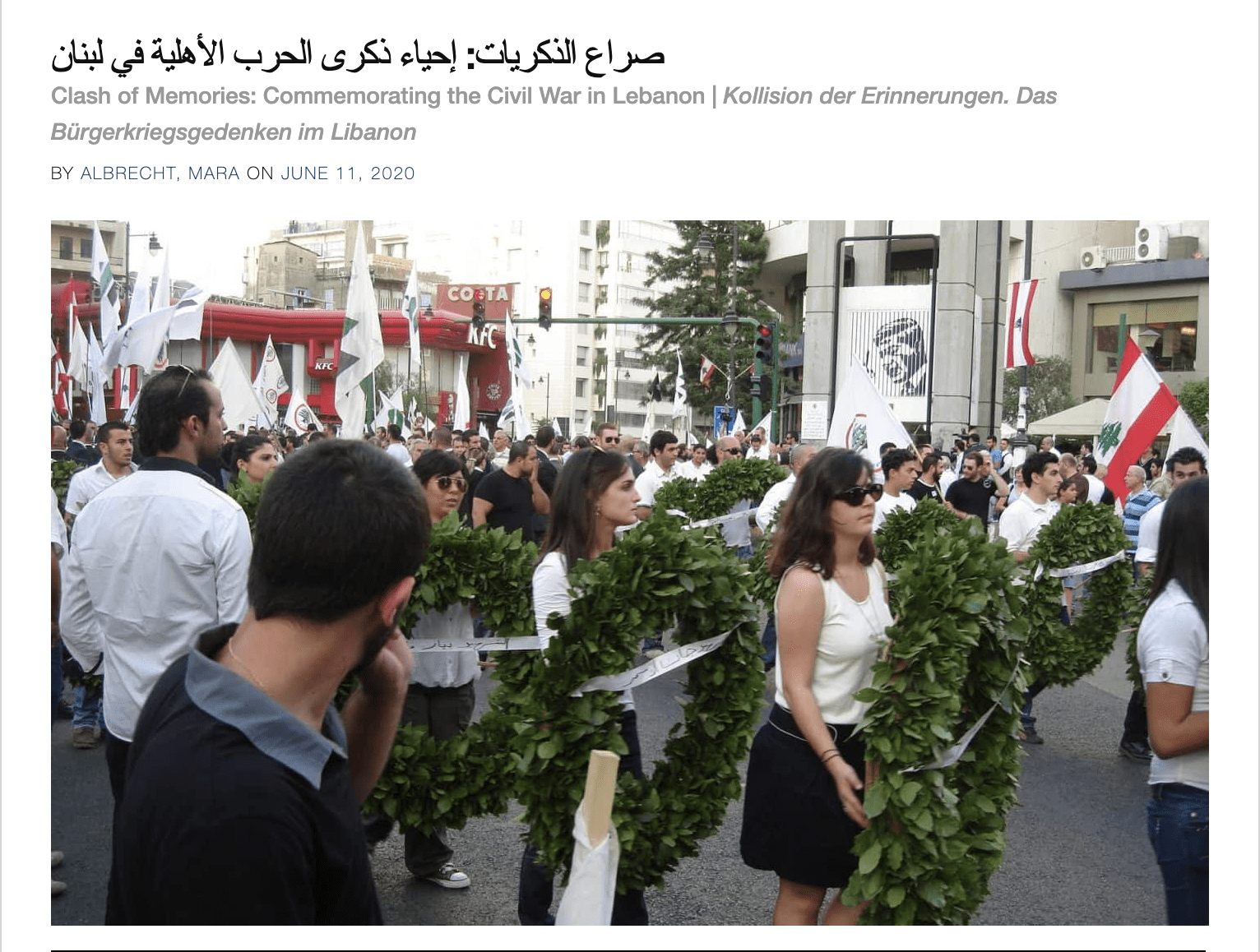

The Taif Agreement of 1989 provided the basis for the end of the civil war and return to political normalcy in Lebanon. The first post-civil war government issued the General Amnesty Law, in August 1991, that exempted Lebanese war protagonists from legal liability for all crimes committed before March 28, 1991. Accordingly, all political leaders were granted retroactive immunity. Mainstream oral tradition often paints the Amnesty Law as a collective moral agreement drawn by the public to pass pardon and turn a new page. Forced amnesia was imposed by the public authorities and their associated media outlets. National processes for enacting transitional justice and dealing with the troubled past were never launched. Three decades later, the civil war period is still not taught in official history curricula; numerous reform attempts to draft a comprehensive account of the war have failed due to multi-sided partisan revisionism. Despite of, and arguably due to this pervading state-sponsored amnesia, sectarian tensions prevail. While some governmental and non-governmental initiatives attempting to deal with the memory of the war have taken place at smaller scales, no significant improvements in dealing with the country’s bloody past have been made. One of the main reasons for the failures and modest success of dealing with the past was the lack of continuity and consistency. Most attempts would emerge on a short to medium term and lack a fundamental presence in the community where they took place.

Explore the memory scene in Lebanon:

Curatorial focus

A staggering amount of artworks has been produced in Lebanon addressing the fifteen year civil-war and the amnesia that accompanied the era after its official end at the beginning of the 1990s. These artistic projects contained within them various inquiries pertaining to the writing of a violent and conflicted history, and to the possible modes of praxis against an amnesiac amputation from said history, such as: What happens to artistic and cultural work across violent historical rupture? What does it mean to insist on revisiting such a contentious period of time, when its mere mention is often framed as inciting of sectarian tensions? How to avoid lapsing into liberal human rights discourses that reduce wartime and peacetime into clean-cut temporalities, obfuscating the structural violence that is inflicted across both? These questions are still central to present-day discussions about dealing with local histories, wartime narratives involving multiple conflicting ethno-sectarian groups, and processes of enforced amnesia.

Despite the relevance of the investigations carried out by the concerned practitioners, much of the artistic work produced during the years following the end of hostilities remained rather limited in its scope of dissemination in Lebanon, despite great acclaim and currency in international platforms, exhibitions, and publications. A proper materialist reading of the conditions of production and circulation of the artworks in question avoids attributing their limited circulation and reception among Lebanese audiences solely to their formal “inaccessibility,” or their highly conceptual and experimental nature. Instead, it is worth noting that few of the artworks gathered here have received any public funding or support from the Lebanese state, at production or exhibition stages.

Notwithstanding any stunted circulation and local impact at the time of their inception, the works produced attest to the state-sanctioned politics of amnesia and willful forgetfulness enforced since the end of the war. They constitute a record denouncing the absence of a duly diligent collective examination of a troubled common history, of each party’s involvement in and positioning within the victim-perpetrator spectrum. They are works that acted at their time of production as counter-hegemonic vectors, constantly in the way of the postwar image-building process imposed by the state and public agencies, sectarian parties, affiliated media outlets, and private, public, and hybrid development projects such as Solidere.

This first selection of artworks presented at WAMM offers a representative instantiation of the issues at play, employing different formal and conceptual gestures, across diverse media. Lamia Joreige excavates collective memory by soliciting oral retellings of wartime events in Here and Perhaps Elsewhere. Paola Yaacoub and Michel Lasserre tear through the image of a pastoral idyllic landscape to single it out as a location of battle in their photographic series Elegiac Landscapes. Marwan Rechmaoui sculpts a human-scale reproduction of a tower as an ad-hoc memorial of muted crimes, and as a lasting scar, in Monument for the Living. Nada Sehnaoui disfigures a newsprint material through paint and collage, covering words, sentences, and information in order to reconfigure dominant temporalities in her work Painting L’Orient Le Jour. Fouad el-Khoury directs attention away from dominant modes of war coverage in his photographic work, as if war is always-already present yet latent, whilst his work after the war looks at material and landscape traces that act as reminders of the war.

Twenty or so years later on, works produced after the civil war are essential material for any reflection on war and its rejected memory, and on a post-war order no less full of structural and physical violence. The works will be archived and accessible in a direct and purposeful interface with a varied audience. Younger audience members may find specific relevance in the works, by virtue of the historical distance that they are positioned at, at a time of great discussion around regimes of post-truth and their negation of historical and scientific fact. It is our hope that he works selected for WAMM will inspire a spirit of inquiry into the possibility of excavating beyond the surface of official narratives and contribute to dialogues about modes of pursuing an ostensibly elusive historical truth.