The Violence of Memory

Sri Lanka, 2017: Eight years after the end of the war, the memory of violence might be in the past, but the violence of memory is continuously refreshed. The military guise has been shed, but violence still lingers in the everyday. This violence exists in the culture as much as it does in national symbols and institutions. It lingers in conversations, the interactions between people, in casual looks exchanged in the streets. It even lingers in family environments, in carefully and subconsciously crafted self-perceptions, even among the oppressed.

In terms of political philosophy, this violence is an Althusserian Ideological State Apparatus, its subjects, i.e. all Sri Lankans whether majority or minority, are continuously interpellated or ideologically indoctrinated in various sites of institutional power, including family environments and the cultural space.

The ‘violence of memory’ is a violence that continuously seeks to maintain the status quo, ultimately invoking only a single thought; know your ‘place’, and stick to it. It operates largely in the invisible, and when it surfaces, it only does so in the minds of those it actively others. To everyone else, it is merely a ghost in the dark, an illusion conceived of only by the mentally unhinged. People submit out of fear of ridicule, fear for their lives and their livelihoods.

Sri Lanka, with thousands of years of history and heritage, is a country that has suffered enormously from conflict in its post-independence years. Most of it has been driven by the complete stake to the nation laid claim to by its dominant Sinhala-Buddhist majority, represented by the roaring, sword wielding lion in the country’s flag. The war with the LTTE, and the JVP’s Marxist class struggle laid claim to more than a hundred thousand lives. Today, in the post war era, Islamophobia has reached dangerous levels, with many of the global stereotypes levelled against the Islamic faith surfacing in strong institutional propaganda and public discourse. Mass racism and acts of brutal violence is seen against Muslim and Christian minorities, as well as against the economically dispossessed.

Currently the country slumbers in an uncomfortable and tenuous peace. The wounds that have been created by its 30 year long civil war, and the root causes for the same, and the festering sores from its multiple other fears and insecurities are left unhealed. The ultranationalist ideology that has pervaded Sri Lanka’s existence since independence constantly works in the background, looking for an opportunity to break out into a mainstream under pressure from an urgent need to ‘develop’ and ‘progress’ at all costs.

1. A TEARING COUNTRY?

The idea of Sri Lanka as a nation state only emerged in post-independent Ceylon. Before colonialism, the island comprised of rarely unified, fragmented feudal states which relied on alliances of trade and kinship to survive and thrive. The idea of a cosmopolitan nation state held together by symbols, institutions and the notion of democracy never transformed into a peaceful, pluralist ideal. The Sri Lankan flag, the country’s strongest symbol, is tellingly designed with the hierarchy of ethnicities in mind. The fierce lion represents the Sinhala peoples, and cowering before it, slim strips of green and orange represent its two largest minorities, Tamils and Muslims.

March 2, 2015 was the 200th anniversary of the country’s full abdication to the British. On the morning of March 2, 1815, before the agreement was signed, a British soldier took down the flag at the Temple of the Tooth (at the time, it was supposed to have been the so-called ‘Sinhale’ flag, with only the lion in current flag displayed on it), and hoisted the Union Jack. This incensed Wariyapola Sumangala Thero, who promptly took down the Union Jack and re-hoisted the lion flag claiming that it was still the flag of the country until the agreement was signed.

The ultranationalist Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist Power Force) walked into the Temple of the Tooth on March 2, 2015 and tried to pull down the Sri Lankan flag hanging there, at the very place that Sumangala Thero did it 200 years ago, in an attempt to replace it with the ‘Sinhale’ flag. They also demanded that the country’s name be changed to ‘Sinhale’, a state exclusively and openly cantered on the idea of Sinhala-Buddhist nationhood with even the semblance of multiculturalism erased from its identity.

While their power of the BBS is largely diminished, none of the crimes they committed from 2012-2015 against ethnic minorities have been accounted for. The new regime has done little to bring justice to all those hurt by its hate crimes. Instead, the corrosive ideology of the BBS has been allowed to survive and flourish in the fringes, gathering forces and biding its time until an opening presents itself for the organization to once again enter the mainstream.

2. WIJERATNE

Despite the death of tens of thousands and the dispossession of millions, many Sri Lankans enjoyed the privilege of only having to be witnesses to terror. But how has this witnessing transformed us? How has our being passive audiences to atrocities affected our drive to change things? Despite years of suffering, many Sri Lankans still remain indifferent, and do not actively seek to address the core ideologies of the country that repeatedly lead it spiralling back to conflict along lines of ethnicity and class. Many of them have been touched deeply by the conflict nevertheless, even as it remained a constant in their environments, shaping and restricting their lives in unseen ways.

Wijeratne (72) sat staring out from the window the whole time I spent up there with him, we were on the second floor of the restaurant he works at in Ratmalana. This large room was reserved for the workers to sleep in. Small sleeping pallets and piles of clothes littered the floor. Wijeratne gave the impression of having spent all his leisure time staring out at the street, he seemed to derive so much contentment out of the act. He’s been a cook at this restaurant since 1968, moving to the city from Eheliyagoda. From his vantage point in this upper floor room looking out at a slice of a busy suburb in Colombo, he has also seen a lot of Sri Lankan history pass him by.

After nearly fifty years of watching this same patch of street, the biggest change he can point to is the number of buildings that are there now that weren’t there before. There is peace now he thinks, and more prosperity. In July 1983, Ratmalana burned as mobs targeted and killed any and all Tamils they could find, and destroyed their property. People were cut down on that very street. It burned again in 1986, when the IPKF were in Sri Lanka. He remembers how the People’s Bank went up in flames, and the buses that were set alight. In those days you couldn’t leave your home and trust that you would return alive, he says.

His face becomes animated when he talks about the JVP insurrection of 1971. In April that year there were curfews, and things were so bad at that point that he couldn’t even sit at his favourite spot next to the window. They had a vice-like grip on local businesses, Ratmalana was a hotspot of JVP activity. They would shut them down whenever they felt like it. On days like that Wijeratne would work hard in the early hours, cooking a morning meal for hundreds, only to find out that the shop was not allowed to open. The food didn’t go to waste though, a steady trickle of people from the neighbourhood emerged through the back entrance and slowly bought it up. The JVP was masterful in the ability to simultaneously use coercion and leniency in ensuring public loyalty (Ratmalana, 2016).

3. RASAMMA

In 2013 Rasamma was evicted from her home, along with a bare handful of Tamil families in Dambulla who were living close to its main Buddhist temple. The eviction, which happened as a part of a nationwide neoliberal agenda that saw the illegal dispossession of the poor from all ethnicities, is particularly illustrative of the case of a particularly downtrodden and powerless group; ‘estate’ or ‘upcountry’ Tamils that were brought in as cheap labourers into the tea plantations of the British. Their status and rights as ‘Sri Lankan’ has been contested politically, institutionally and socially ever since.

Their land had recently been declared ‘sacred’ in a legal sham and their profane presence was therefore no longer deemed suitable. They were brutally harassed by the military, their basic services were cut off, and where intimidation didn’t go the distance, insignificant sums of money was paid as bribes to sign their homes away. Ironically, their small village also included several Sinhalese that suffered the same fate.

Their kovil, in which they took shelter, was demolished. The statue of their goddess Kali was dragged out and flung into a well. Having no knowledge or recourse to fight, they were forced to leave, beg from extended family and continue surviving in whatever way possible. They have received no compensation or reparations. Many have fallen sick and some have died. Not a few of them, we are told, from depression.

Some of the community, now living together elsewhere, carefully shelters a small altar with a statue gifted to them by a well-wisher in a small room, this is the only place of worship they have left. Tomorrow they will go to Colombo for another attempt at justice from the new regime.

As Rasamma shows us old documents from a bag, a tiny postcard slips out and falls to the ground. It is dated July 13, 1970 and is from the Commissioner of the Department for the Registration of Persons of Indian Origin. In a stabbing twist of irony, it reads: ‘I have the honour to acknowledge receipt of your application for Ceylon citizenship’.

Her thin face is etched with long years of hardship, but her expression is always calm and collected. Her eyes are old and yellowish; watchful and quiet, and her gaze always resigned. Occasionally she will smile. And then you see that she is truly beautiful. Her face, aside from her neat, colourful clothes and graceful posture, is the most striking thing about her.

But I cropped out her face because Rasamma has no right to a face. Why must I allow her to transfix you, to force you to acknowledge her? Why must I dignify her in a picture when we have failed to dignify her in real life? (Dambulla, 2014)

4. THE REAL AND THE VIRTUAL

The internet is a prime breeding ground for hate speech. The first indications of post-war hate rhetoric against Muslims and Christians appeared on social media platforms, mainly Facebook. As several new studies have pointed out, hate speech on Facebook was disseminated over a large number of groups and pages, and mostly in the Sinhala language.

These groups function as ‘echo chambers’, propagating and spreading ideas among like-minded individuals and indoctrinating others into their folds. In the highly internet savvy environment of Sri Lanka, many people depend on social media and instant messaging services for news and gossip, especially given the perceived ineptitude of mainstream media. This leads to the fast spreading of rumors and false reports, and the increasing viewing of the other through the lens of social media.

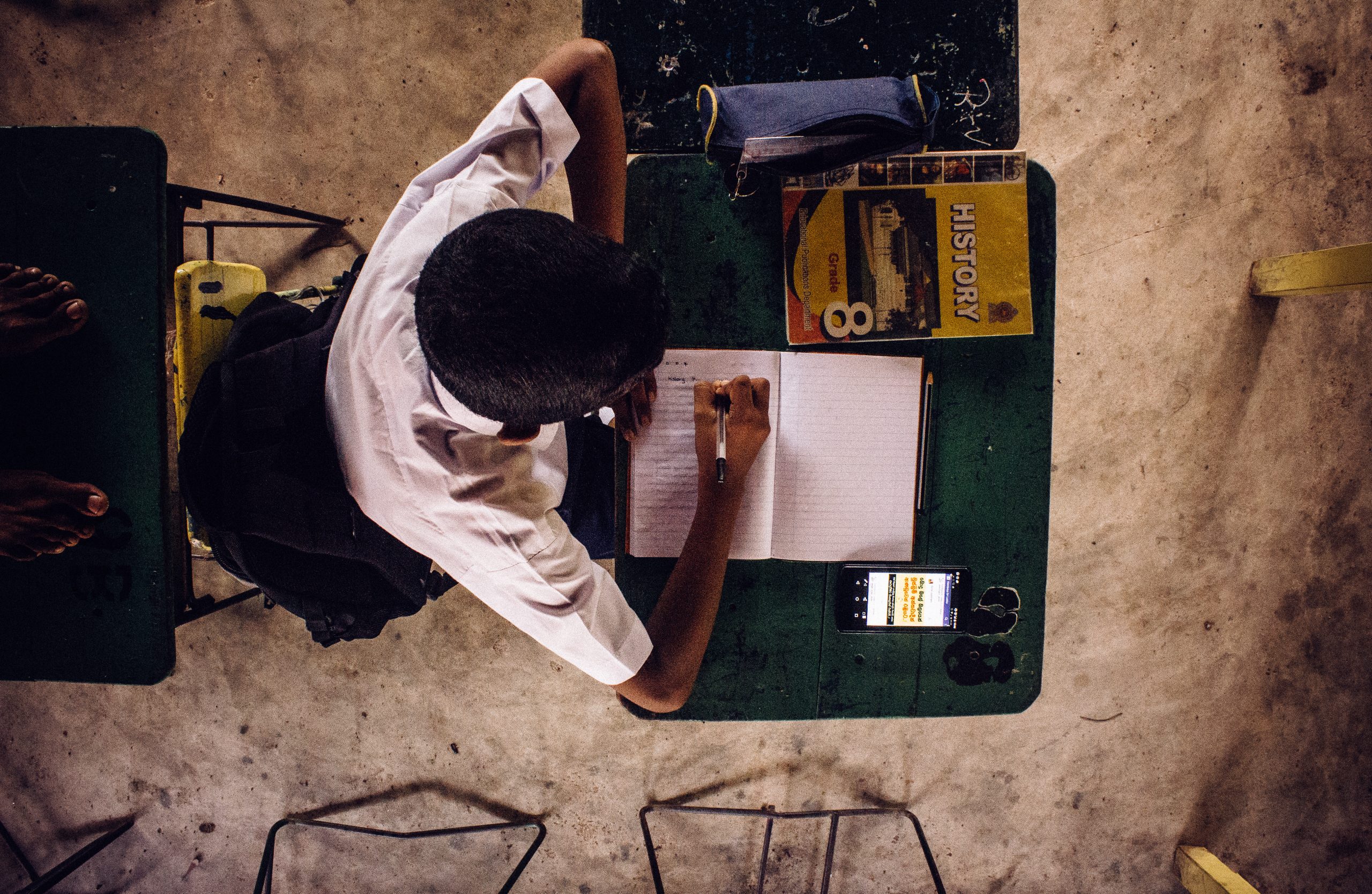

One of the primarily results of widespread and organized hate speech is the indoctrination of the young and innocent. The subjects taught in school, like history and social studies, are woefully inadequate and highly damaging. The subject matter that is exceedingly boring when it isn’t being highly jingoistic. Schools function as sites of indoctrination that perpetuate the social divides and problems which contribute to conflict.

One of the biggest dangers that escalates this phenomenon is the vast availability of hate speech and propaganda over the internet. Highly dangerous in a social environment which refuses to talk about, let along critically examine, its own history and circumstances. Sri Lanka, having come out of a civil war that spanned an entire generation of youth, is in danger of repeating its mistakes if it continues to refuse to learn from them.

5. BUDDHISM AND PEACE

Buddhism is widely regarded as an ideology that is peaceful. But what happens to Buddhism in a post-colonial society dealing with ethnic, economic and political unrest, finding itself in a neoliberal global context that thrives on greed and capitalism? Would Buddhism provide a provision to justify all the violence that would result? Does Buddhism have a ‘just war’ thesis?

The conflation of Buddhism with the Sinhalese identity has always been an element that has given it a special status, tying it to both the Sinhala race and its langauge. The apparent endangerment of the Sinhala language is an old issue in Sri Lankan society that pre-dates colonial independence; the Sinhala language, being spoken only in Sri Lanka, has for this reason long thought to contribute to a minority complex in the country’s majority. In the post-war climate, language oriented paranoia was accompanied by conspiracy theories to the affect that the Sinhalese race (due apparently to its own flagging birth-rates and the escalation of that of the Muslims’) were being outnumbered in their own country.

A mati pahana (clay lamp) is usually lit by Buddhists as an offering of light, the flame is a symbol of the impermanence of life. In Aluthgama in 2014 the light lit by individuals claiming to protect the dhamma, raining down in the form of petrol bombs thrown into houses, only served to extinguish the life of innocents.

Sri Lanka’s Buddhist extremism mirrors in many ways the violence of the 969 movement in its close Buddhist neighbor, Burma. Where monks justify the most heinous crimes against Rohingyas. In Tibet, monks were authorized to disrobe in order to fight the invading Chinese, to them the biggest sacrifice was not laying down their lives but laying down their accumulated good karma by the very act of even touching a weapon.

Being a Muslim, I know what it feels like to see your beliefs used as a scapegoat by some for unimaginable hate and violence. With the mainstream mostly preferring comfortable silence, the social realm of religion is open to the predatory forays of extremists and self-interested politicians alike. (Statues in disrepair at a temple in Dambulla, 2014)

Description

In this photo essay Halik is touching upon some of the fundamental issues underlying the everyday violence people experience. We need little or no additional information to understand the photographs, since Halik explains this so well himself. His concern is palpable: Even though the war has been over for sometime, there are deep divisions which are perpetuated. There is a sense of urgency in his work. He is unable to leave them as just images, but provides the context within which we can understand them better, and thereby enter into a dialogue about the issues raised. Halik’s background in journalism is clearly adding weight to his work here.

The work has been shown and published in the following

‘Young Subcontinent’ Serendipty Arts Festival Goa 2016

‘In search of stillness’, Edinburg Festival Fringe 2017

‘Recurrence: a conversation among six artists’ Lionel Wendt Gallery Colombo 2019

Here are installation views from exhibitions:

Press

Remembering Lasantha six years on: Launch of photo-essays on Sri Lanka